Letter to S.S. Kotelianksy | From Constantine Bay, Padstow, Cornwall | 11 December, 1933 | Page 4 of 4

Notes & Transcript >

Letter to S.S. Kotelianksy | From Constantine Bay, Padstow, Cornwall | 11 December, 1933 | Page 4 of 4

Constantine Bay.

Padstow.

N. Cornwall.

Dec.11th, 1933.

Dear Kot:

I like to think of your curses resonant all over St John’s Wood – though, or because, this way of letting off is one I’m wary of. I believe I’m more patient than an ox & much more patient than Griselda, whom I suspect of motives. It is no virtue, nothing more than dislike of certain kinds of destruction, & a need, perhaps, to keep steam banked for the perpetual contest with obstinate inanimates. Perhaps cursing is a man’s business; (“hear, hear” Arthur Schop. unrepentent in Purgatory) yet my patience is as nothing beside Alan’s.

I have spent my spare moments with Kastein, who seems, to me, because he is enough of a mystic to be also an intensely practical ‹man›, to have written exactly the book that is now needed. He puts all he handles in a true per spective & I am sure large numbers of Gentiles will welcome him as gratefully as those he addresses; & though their cheeks may burn for different reasons, their hearts will ache for the same.

His thunderous German is a joy to me after months of French: of dodging corps de ballet of superfluous prepositions, d’ailleurses & ainsis & cepend ants curtseying & pirouetting all over the page, for the sole purpose of reminding the reader how elegant is French prose. So concentrated on ele gance, that it has forgotten, if ever it knew, the lovely art of grammar. Go as you please, “au courant de la plume”, slip-slop: “Ce, c’est, ce sont” as

[page 2]

introduction to no-matter-what, or referring to God knows what in whatever precedes. Their famous logique & clarté: the child’s play of bigots. Where is my patience? These, I perceive are things that can make me hit out.

Now Kastein knows deeply & doesn’t hold that brevity is invariably the soul of wit. His style’s one fault (I find the way he clears the ground right & left as he goes, admirable) is the natural defect of its quality: too great explicitness, making the reader sometimes cry for mercy. Something of this might disappear in English, be mitigated at any rate by the absence of strings of words following the sentence-climax, necessitated by the quaint German construction.

To-day, I hear from Mr Cohen that they would like me to translate, at my full fee, (I’ll pray daily for you, Kot) if Dr Kastein will accept the terms of their offer. They want the book as soon as possible & I have asked them to telegraph if I am to proceed.

And here, for you, is Pilgrimage, which has, so to speak, never been published. Ten chapter-volumes have found their way into print, into an execrable lay-out & disfigured by hosts of undiscovered printer’s errors & a punctuation that is the result of corrections, intermittent, by an orthodox ‘reader’ & corrections of these corrections, also intermittent, by the author. (Whose system, if such it can be called – Beresford discovered & pointed it out to me – cannot be bad, or a dissertation I wrote after Beresford’s dis covery had made me punctuation-conscious, would not have been incorporated by Columbia University in their volume for the use of

[page 3]

students of journalism). The order in which these “chapters” appeared is apparently undiscoverable either by booksellers or librarians. They offer, as the first, or the latest, any odd volume they happen to have. The intervals between their appearance has [sic] been disastrously long. Yet, at snail’s pace, they all go on sell ing. In every one of Duckworth’s biennial statements each one of the volumes appears; & the last year or two has shown a slight increase. Letters, & reviews, indicated that young persons liked the last volume, who had read none of its predecessors. I believe, all told, that a decent, corrected edition_ in the form of two, or three, of the short volumes bound together – would pay its way. Duckworth agrees, but is prevented from venturing, by having (myste riously) set the books up in varying types. I hold his promise to release me. But the publisher taking over would have to acquire his stock, not large, and settle my overdraft on Duckworth, once £300, reduced, by attrition, to some thing like £60. In regard to the first volume, I would accept a small royalty agreement. If it did fairly well, my share in the next to be larger.

One or two publishers have come rather near to making the venture. A relative of Gollancz told me that he, G., was so moved to wrath by Gould’s “pert, cheap” Observer review, ‹of my last book,› as to be nearly per suaded; but decided in the end that he “could not afford the luxury”. Grant Richards, when he started as Toronto, wrote to me. When he saw my sales record he said it made him want to weep, but it also prevented him from specu lating with the funds of his backer.

A real edition by a

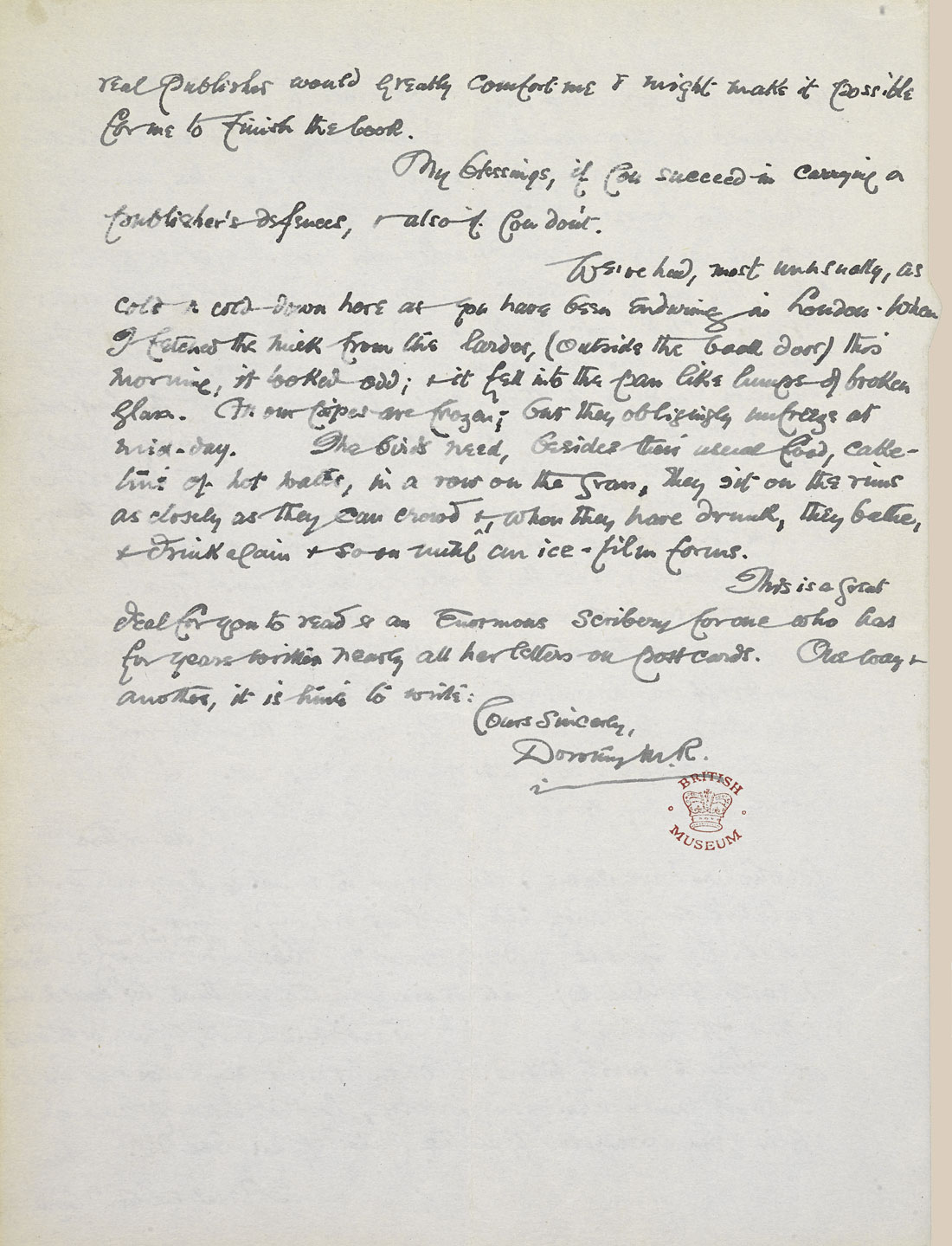

[page 4]

real publisher would greatly comfort me & might make it possible for me to finish the book.

My blessings, if you succeed in carrying a publisher’s defences, & also if you don’t.

We’ve had, most unusually, as cold a cold down here as you have been enduring in London. When I fetched the milk from the larder, (outside the back door) this morning, it looked odd; & it fell into the pan like lumps of broken glass. All our pipes are frozen; but they obligingly unfreeze at mid-day. The birds need, besides their usual food, cake-tins of hot water, in a row on the grass. They sit on the rims as closely as they can crowd &, when they have drunk, they bathe, & drink again & so on until an ice-film forms.

This is a great deal for you to read & an enormous scribery for one who has for years written nearly all her letters on postcards. One way & another, it is time to write:

Yours sincerely,

Dorothy M.R.

Notes

- S.S. Koteliansky was a translator and editor, who maintained relationships with many modernist writers: Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, and D.H. Lawrence as well as Dorothy Richardson. He lived, in the 1930s, at Acacia Avenue, St. John’s Wood, London.

- ‘Griselda’ is unidentified.

- ‘Arthur Schop:’ refers to the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. Richardson objected to what she saw as his pessimist misogyny.

- ‘Alan’ is Richardson’s artist husband.

- ‘Kastein’ is Josef Kastein. Mr Cohen is Dennis Cohen of the Cresset Press. Richardson agreed to translate Kastein’s latest book, which appeared as Jews in Germany in 1934. The ‘months of French’ refers to her ongoing translation project, André Gide: His Life and His Work by Léon Pierre-Quint, which was to be published in London by Jonathan Cape and in New York by Knopf in 1934.

- ‘Beresford’ is the novelist J.D. Beresford, who was a friend of Richardson’s and had championed her book from its beginning.

- The ‘dissertation’ about punctuation was her article ‘About Punctuation’, published in the Adelphi in April 1924. The inclusion of this essay in a textbook for journalism students has not yet been verified.

- ‘Gollancz’ was Victor Gollancz, whose publishing firm was founded in 1927. Gerald Gould was a writer and journalist, and was the fiction editor for The Observer newspaper. He was also chief reader for Victor Gollancz, Ltd. His review of Dawn’s Left Hand, in November 1931 criticised Pilgrimage’s length and complexity, saying that Richardson ‘appears to take for granted that we have little in life to do except to follow with interest the minutest reactions of Miriam’s mind’.

- Grant Richards was a novelist and publisher.